"Groin Strain" not....

From the earliest days I can remember, football was more than just a game—it was a way of life. I didn’t just play football; I breathed it. Morning, noon, and night, it coloured my world with excitement, competition, and camaraderie. Though I wasn’t destined to rise through the ranks with jaw-dropping talent, I had just enough spark to keep the passion burning. It was never really about glory—it was about joy.

Every break and lunch hour became sacred rituals of muddy knees and roars of celebration with my mates. Our playground was our stadium, and those fleeting minutes of play were as treasured as any professional match. By the time I reached Year 9, that love hadn’t waned in the slightest. If anything, it had matured. Football was no longer just something I did—it was part of who I was. It taught me about teamwork, resilience, and the kind of happiness you find when your feet are flying and the ball’s at your command.

It was during one of our usual break-time matches that I first felt it—a twinge, just a flicker of discomfort in my groin. I brushed it off, thinking nothing of it. After all, I was mid-game, adrenaline humming, surrounded by laughter and the clatter of boots against pavement. The game called louder than any warning sign my body was sending. But over the next few weeks, that twinge took root and began to grow. The pain sharpened, and something felt... off.

I started noticing small changes. My leg, once fluid and fearless, began to stiffen. It didn’t respond with the same ease I’d always taken for granted. The freedom I’d known—the one that let me fly down the pitch or twist past a defender—was slipping away. It wasn’t dramatic at first, just enough to cast a shadow over the lightness that football had always brought me. I didn’t want to admit it, but something had shifted.

Concerned but not alarmed, I told my mum about the stiffness and the growing discomfort in my hip. She wasted no time and got me an appointment with the GP for the following evening. I didn’t expect much to come of it—I figured I’d be told to take it easy for a bit and everything would sort itself out. And in many ways, that’s just what happened. The doctor examined me and confidently diagnosed a simple groin strain, something apparently common among young footballers.

We left the surgery feeling satisfied. It was the kind of answer you want to hear when you’re still buzzing with dreams and desperate to be back out on the pitch. I was given a plan: rest, recuperate, and gradually ease back into play. I promised myself I’d stick to it. I believed everything would return to normal, that this was just a minor hiccup in the middle of my football story. Over the next two to three weeks, I did my best to follow the doctor’s advice: no football, no PE. For someone whose limbs were tuned to chase balls without a second thought, it felt strange—like trying to ignore muscle memory. But I gave it a real go. There were moments when instinct kicked in, when a rogue ball bounced my way and my foot twitched with the urge to control it. Still, I held back. Most of the time, I managed to resist the call of the game.

It was hard watching my mates play without me, their laughter echoing across the yard as I sat on the sidelines pretending not to care. I hoped that the short break would be enough—that soon I’d be back where I belonged. But a quiet worry had started to settle in, one that crept in between the reassurances and the waiting. Something didn’t feel quite right.

As days passed, the ache didn’t fade—it worsened. The stiffness clawed deeper, and I felt my body resisting movement that once came naturally. Still, I tried to hide it. I kept insisting things were improving, clinging to the hope that maybe it would all ease up on its own. But my limp betrayed me—louder than any words I could offer. It was subtle at first, but eventually impossible to disguise.

Mum saw through me, as mums do. Her concern grew alongside mine, and finally, she sat me down and convinced me to see the GP again. I agreed, half-relieved that someone else was taking charge. She phoned the surgery, but my regular GP wasn’t available this time. Instead, we were offered an appointment with a locum doctor. Mum didn’t hesitate—she booked it, hoping for clearer answers and a fresh perspective.

I could feel it in the air that day—something different. It wasn’t just another check-up. This time, it felt heavier, like my body was quietly trying to tell me something that neither I nor the first GP had quite caught yet. As I headed to the appointment with the locum doctor, there was that silent tug inside me: part dread, part hope. Maybe they’d confirm the groin strain again and everything would be fine. But maybe they wouldn’t.

Sitting in that waiting room, surrounded by the hum of fluorescent lights and the distant chatter of the reception desk, it was impossible not to reflect on how far I'd come from those carefree kickarounds with my mates. Football had always been freedom—pure, joyful movement—and now even walking felt compromised. I was about to face something unknown, something that would redefine my relationship with the game I loved and with myself.

My name was called. It was time—time to face whatever had been causing this persistent pain. As I stood and walked toward the consultation room, my steps felt heavier than usual, weighted with uncertainty.

I entered and was met by a doctor who looked as if the day had wrung him out. His hair was tousled, his collar slightly askew, and his tired eyes flicked up from the monitor as I came in. He didn’t match the polished image I had of most GPs. No, he looked more like a hospital doctor who had spent hours navigating crisis after crisis. Still, there was something quietly reassuring about him—a sense that he’d seen it all and wasn’t easily shaken.

The room was dimly lit, the blinds only half-open against the fading evening sun. A faint trace of antiseptic lingered in the air. I sat across from him, trying to steady my breath, the buzz of fluorescent lights above only making my heart race faster.

He asked a few initial questions, his tone clipped but not unkind, and began typing without meeting my eyes. Then he turned to me and said, “Tell me about the pain.”

That’s when I knew—this wasn’t going to be a routine visit.

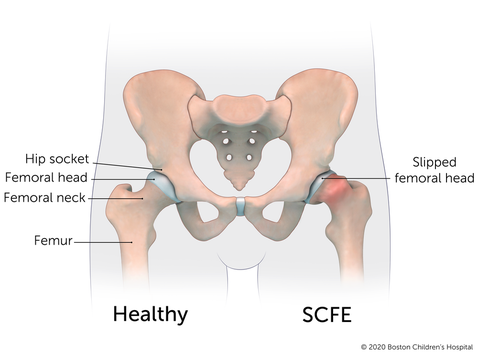

In England, Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis (SCFE)—also known as Slipped Upper Femoral Epiphysis (SUFE)—is one of the most common hip disorders affecting adolescents.

🦴 What It Is

- A condition where the head of the femur (thigh bone) slips off the neck at the growth plate.

- Often occurs gradually during growth spurts, especially in children aged 8 to 15.

- Can be stable (child can still walk) or unstable (unable to walk, higher risk of complications).